Oh, I can remember, all right. Every single thing. I’ll tell you what happened. I’ll tell you how he collected me, like an old clock, like a piece of memorabilia. I remember every detail of that godawful day. I think of nothing else.

***

It was a Saturday, in September. The year was two thousand and thirteen.

It was a restless sort of day, the wind flinging things this way and that, birds fighting to stay on course, the trees blowing about like masts at high sea. A roaring in the air, sometimes as loud as a freight train, made it hard for us to talk, so we bent our heads into the wind and fought our way forward.

Whether or not it was the distraction of the untidy weather, or twisted branches flying unexpectedly upwards from the path, or whether there was something more calculated about the meteorology that day, none of us will ever know. But there was a cry, and a crash of foliage, and down she went, straight onto her stomach, with her right leg folded underneath her like origami.

‘Are you all right?’ we both said, shouting above the buffeting wind. Hans leaned over and tried to pull her up. Laurel cried out, her face racked with pain.

‘No!’ she managed to say, between yelps and gasps.

We helped her get her rucksack off her back, and dropped our own onto the ground beside her. She put her arms around our shoulders and the two of us managed to get her upright, but there was no way she could weight-bear on that right ankle. We hobbled together a few feet, and Hans and I looked at each other over her head.

‘I don’t think it’s broken,’ Hans said, helpfully.

I looked around us. Miles of woodland stretched away on every side, canopies swaying violently to the symphonic crescendo of wailing wind. Nobody in sight. No way of telling how far to the next habitation, the next village, the next hiking party.

I suggested we rest. ‘We can try again in a bit.’

There was little else we could do. Laurel sat on a fallen tree trunk, massaging her ankle and grimacing. Hans leant against a sycamore and threw a handful of seedpods into the air so that they spun in a crazy dance before scattering into the undergrowth. I glanced at my phone. Still no signal. My watch read 4.30pm. Not a good time to be in this position.

‘I’ll tell you what.’ I spoke decisively. ‘Let me have a look around, just see if I can spot anyone else. They might be able to get a signal. Or know how far from the nearest house we are.’

We knew we were on a little-used path; we had chosen it deliberately. It had felt like the wild. Like an England from the past, where you might see a bear or a wolf, where wild boar were plentiful and herds of deer grazed just over the next rise. No villages, no hikers, no satellite signal.

‘Come back in ten minutes,’ said Hans. ‘One of us needs to stay with Laurel.’

I rolled my eyes at him and set off, branches whipping my face and pigeons erupting from the canopies with explosive whirring of wings, struggling to fly straight in the fury of the wind. There was the smell of mould and damp so familiar to woodland, of moss and secret holes where badgers hide and wait for dusk, and spiders spin thick dense webs. Feathers and seedpods somersaulted into my hair. I skirted brambles and clambered over a fallen oak tree, its roots upended and grasping the air like a dying breath. There was nobody anywhere that I could see. In these stormy conditions there may have been an entire village around the next bend in the path, and I would have been none the wiser.

I was about to turn back when I saw it. Through the densely packed trunks, a building. A barn? A house? I estimated how far from the path. And decided to investigate.

It was a house. A stone house, planted deep and stolid in a clearing, steep gables at the front, an old oak front door, whitewashed lintels and a fat chimney from which I saw, to my relief, a spindle of smoke emerge before dispersing in the wind. At the back of the house I guessed there was some kind of garden, flanked by huge hedges which extended out from the house to about ten yards on either side before turning away from me out of sight.

I never even had an inkling. I never knew that at that moment I had a choice, to turn away and pretend I had never seen the place, to return to my friends and wait in the woods all night long if we had to, until somebody found us. There was no sign from heaven, no wail from the wind, no sinister crow landing on the roof and staring me down. And so such choices pass us by, and our lives are never the same again.

I ran all the way back to the others. They brightened immediately at the expression on my face. ‘Do you think you can make it there?’ I said to Laurel, when I’d finished describing the distance. ‘If you lean on us both?’

Laurel’s face took on a new determination. ‘I’ll make it,’ she declared, and tried to stand. The ankle still would not bear her weight. Hans and I threw our rucksacks into a large patch of brambles and prodded them out of sight. Together the three of us made our way, slowly, slowly, down the overgrown path.

Eventually, there it was, squat and welcoming and still piping smoke. We grinned at each other, and inched our way across the wild grass, flattened in the gale like hair plastered on a scalp, to the front door with its discoloured iron hinges and heavy iron knocker. I lifted the ring and let it drop, twice. The noise thudded distantly, a bass note to our huffing breaths and the wheezing of the wind in our ears.

The door was flung instantly open, with a kind of exuberance. A man stood there – impossible to tell his age – smooth-browed, pale-eyed, with a wide and welcoming smile. Before he even saw us. Before he even registered us. As if he had been expecting us for a long, long time.

‘Why, hello, hello!’ he cried, and stood to one side. ‘Come in, please do come in!’ Then he saw Laurel, and the way we were supporting her. ‘Oh my, what’s happened here? Mother!’ He threw the name over his shoulder. ‘We have need of you!’

As we staggered indoors, the wind caught the door and slammed it shut behind us with a resounding, devastating crash. There was a brief snuffling under the door, and then nothing. The man shot three bolts across the door into their slots, and as way of explanation, said, ‘Such wind! Never known anything like it!’

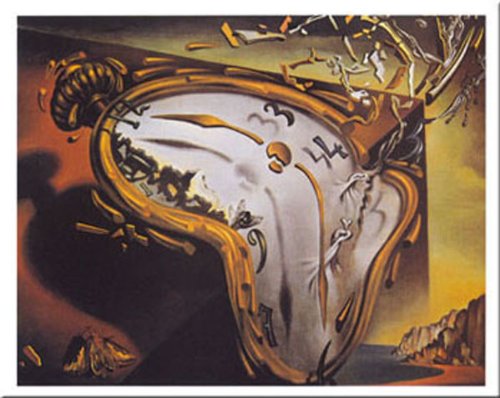

At first the silence was so loud it hurt my ears. Then, gradually, I became aware that it was not silent at all, but full of tiny noises, from every direction, tiny teeny noises like crickets at dusk. Clocks.

It was such a relief to be out of the noise and rage of the wind, such a relief to have found help, that at first I barely noticed the clocks. A brief scan of the hall and the adjoining room revealed timepieces on every surface, small bright brass ones with jauntily swinging pendulums, others larger, sombre and dark-wooded, and two enormous grandfather clocks that made a deep, echoing ‘thwock’ sound as the pendulums rocked to and fro, to and fro.

We explained the situation as best we could, when our host’s mother shuffled up the hallway, saw Laurel, and shuffled away again. When she returned, medicine box in hand, she did not greet us, but immediately leaned down to feel Laurel’s ankle while Laurel sat on a chair, sucking in her breath every time arthritic fingers prodded a tender spot. The woman’s head had barely any hair left on it, and reminded me of a turkey chick before it is fully feathered. She fished out a bandage and began to wrap it expertly around the ankle as if she did this every day.

All the meanwhile, her son talked and talked. ‘So exciting,’ he said, ‘to hike in these parts, just striking out! Striking out to heaven knows where, never knowing where you’ll end up – and here you are! At our little nest in the woods! What a day, what a day……’ and here he raised his tiny eyebrows so high they disappeared under his generous thatch of blonde hair. ‘Well, you simply must stay for dinner.’ He raised his hand over our protests. ‘No, there is to be no argument. You are tired, you…’ indicating Laurel ‘… are injured, and it will take a good while to get someone up here to help you out. You’re going to need a stretcher, my dear, and a veritable team of fit young men to carry you out!’

My heart sank. ‘You don’t have a car?’ At that point, his mother glanced upwards, her gaze momentarily catching my own. It was unreadable, but there was something in it, something I felt I should understand. ‘A car?’ The son laughed like a machine gun. ‘Not for us! We haven’t had a car since – oh, when was it, mother? Five, ten years ago? Far too much trouble. No, we have a friend in the next village; he comes once a week to take mother to the shops and restock our little nest with all the food we need. We’re rather proud of being… self-sufficient, shall we say!’ He chortled, and indicated a telephone which sat on a polished walnut cabinet. It was the oldest phone I had seen for years, like something from a wartime film, black and angular with a manual dial, and when I picked it up it weighed a ton in my hand. The tone was dead.

‘Oh,’ said our host dismissively, ‘must be the wind. Never known a wind like it! Try again later, my dear. Come sit down, sit down.’

So we followed him to the living room. Our host sat down in a rocking chair, swinging back and forth rather violently, like a child barely able to contain his excitement. Laurel was helped to a chair nearby, her leg propped up by a small stool. The room was rather murky and once again, on every surface crouched a clock of some description. I tried my phone again; still nothing. I ducked back out to the hallway to try it there, but still no luck. When I returned to the others, Hans was saying, ‘I’m Hans, this is Laurel. You are…?’

‘Call me Harold,’ our host answered promptly. ‘I can’t tell you what a pleasure it is to have guests. Mother’s thrilled. You can’t imagine how quiet it is, living in this place.’ As if on cue, the clocks began to strike the hour, some simultaneously, others sequentially, from high tinny tones to deep resonant ones, from every direction and every dark corner in the house. We looked at each other and laughed. Harold echoed us, his eyes crinkling and vanishing into his head.

When peace reigned once more, Hans spoke. ‘I was just wondering, what is it you do? I mean, do you even have internet in this place?’ So, he’d noticed the archaic telephone as well.

‘Ah, me? I’m a collector!’ announced Harold triumphantly. ‘And what, you might ask, do I collect?’ He waved his arm around him, caressing the ticking machines with an affectionate gaze. ‘This one, for instance,’ he said, rising to indicate a clock that had a globe of the earth poised above it, ‘turns the globe on its axis at the same speed that the earth actually turns. Fascinating. Found it in Vienna many years ago. Bought it from a dealer for next to nothing. He had no idea of its value. His loss, my gain!’

‘Do you sell them on, then?’

‘Sell them? Oh no, never. Well, almost never. A collector is a collector. I collect for the sheer pleasure of the exercise! I am not a dealer, not a businessman, or an investor. There aren’t many of my kind left in the world, you know. Such an avaricious society we live in, don’t we?’

‘Where are you from?’ I inquired. ‘Originally, I mean.’

‘Oh, here and there, here and there,’ Harold said in an offhand way, and turned to his mother. ‘Dinner, mother?’ She nodded, blank-faced, and left the room. ‘Yes, my work takes me away from home for long stretches at a time, which doesn’t make mother happy, not happy at all. But there you are. Such is life.’ He raised his glass. ‘Welcome, guests!’

‘I’ve just remembered,’ I said, as we drank from our glasses, ‘the rucksacks. We need to go back to get the rucksacks.’ We explained where we had left them, and Hans half-rose from his chair. Harold waved him down. ‘Not yet, not yet,’ he said, ‘we have plenty of time.’ Hans sat down again, a little uncertainly. Harold was watching me, with a smile.

‘After dinner, we all three can go,’ he said. ‘What say you all?’

‘Sure, good idea,’ said Hans, sitting down again.

Laurel began to ask him about the other clocks in the room, and I leaned back and closed my eyes. The clocks whirred and tocked, and voices droned on, and I stopped listening. I was tired, and hungry, and glad to be warm.

Dinner arrived earlier than I expected. I had begun fiddling with my phone again, trying for a signal in different parts of the room and the hallway, when the old woman appeared in the gloom with a large and full tray. When she saw me in the hall, she put the tray down with shaking hands, and turned to me, her rheumatic eyes wide. She lifted a chain over her head, and I saw there was a gold cross hanging from it. Then she leaned forward, breathing heavily, and pressed the cross into my hand, closing my fingers over it.

‘No, I can’t possibly,’ I said quickly, but her fist around mine was surprisingly strong. She was straining towards my face, so that I could smell her garlicky breath, and then she whispered in a hoarse, broken voice, seven words. Seven words that I could not believe I had heard.

‘That man – is my great, great, grandfather…’’’

Harold appeared at the doorway. The old woman moved with surprising haste back towards the dinner tray. He eyed my closed fist, and put out his hand. ‘May I?’ he said with an edge to his voice. I opened my hand reluctantly. He picked up the necklace and waited until his mother had vanished into the room with the dinner tray, avoiding his gaze.

‘I should explain,’ he said.

‘Nothing to explain,’ I said, her words still echoing like gongs in my head.

‘Oh, but there is,’ he said. ‘My mother, bless her dear soul, has in the last few years begun to – shall we say – decline. You know what I mean,’ and he tapped his head. ‘She ought to be in a home, but I won’t have it. That’s why we live here, far from social services and all that. You understand? And she will insist on giving away heirlooms to various and sundry that she meets,’ and quickly added before I could say anything, ‘yes, heirlooms. This one is very old. Belonged to my great-great-grandmother. Poor dear, she thinks she’s giving them away to her daughter, or son, or someone or other. A great pity. But what can you do? I’m sure you understand. It’s very difficult.’ Without waiting for my response, he slipped the cross into his pocket and invited me to return to the dinner room, his smile reaching from ear to ear, but not touching his pale eyes.

The table was set. There were three steaming dishes, plates, cutlery and wine glasses, and a bottle of wine caked in what looked like a century of dust. I had lost my appetite. There was something going on here. And we needed to be out of it.

I looked at my watch. Six o’clock. ‘I think I’ll just check the phone again,’ I said to nobody in particular, and ducked out. I picked up the receiver. Still no signal.

Slowly I went back to join the others. They were deep in conversation about Austria’s antiquarian bookshops.

After dinner, which I could barely eat, more wine was brought out. I did not touch it. Eventually, Hans looked at his watch. ‘I suppose we should go and get those rucksacks,’ he said reluctantly, then shook his wrist. ‘Watch seems to have stopped.’ Laurel slapped him on the arm. ‘That’s so weird! Mine stopped just before dinner!’ They compared watches, like children comparing prizes, gleeful that they’d received the same one. ‘Oh well, never mind,’ said Harold cheerily. ‘There are plenty of clocks here to tell the time!’ At which there was much guffawing and clinking of glasses.

But as my gaze wandered idly around the room, pausing briefly on the clock faces, I noticed something alarming. The second hands were moving backwards.

Quietly I stepped out of the room. It was the same in the hall; everywhere the same.

The panic that took hold of me may have seemed disproportionate at the time. Although, from the perspective of now, I’d say it wasn’t nearly proportionate enough.

I had to talk to the others, alone. I had to tell them the words of the old woman, the sudden, convenient story of her dementia. And now the clocks. I needed to leave, to get out. But I couldn’t leave the others here. They weren’t safe. In what way they weren’t safe, I couldn’t say. But I knew it for sure. In my bones.

I looked at my own watch. It had stopped. Around me the clocks clunked and whirred and chirruped on, and I wondered at myself, that I had ever thought it quiet in this house. I also wondered what I should do next. The front door may be bolted, but outside it was blowing a gale, and getting dark, and surely we were better off in the warmth, with food in our bellies and a place to spend the night?

But I could not shake the foreboding, the shadow that whispered in my ear, fingered me coldly on my neck.

Making my way back to the living room, I became aware that the voices had fallen silent. My steps slowed. I listened. Softly, I pushed the door ajar. The old woman was gone from the room.

At the table, Laurel and Hans sat, their heads fallen forward onto their plates. Asleep, or dead, I couldn’t tell which. Harold had his back to me, and was carefully – tenderly, almost – folding back a lock of Laurel’s hair from a pool of gravy, tucking it behind her ear.

I did not wait to see what would happen next. I had seen enough. I ran.

Down the hallway, through a doorway at the end, into a kitchen, cramped and claustrophobic. I could see the back door, and dashed to open it. A cold gust of evening air rushed in and slapped me across the face. I could only think of one thing. I had to get help.

Nobody followed.

Outside, it was the time of day when the edges of things smudge together and the world is a mass of imprecise shapes with monochromatic colour, lacking definition, lacking substance. The wind had dropped at last, but there was still a breeze, and I became aware that I was standing in the garden – well, a garden of sorts, surrounded by high hedges, whose leaves rattled and twitched and fidgeted nervously.

The way out was not clear. On both sides of me the hedges reared high, twice my height, and met the walls of the house in a large tangle of blackberry and nettles, an impenetrable barrier, especially in the dusk. There was a broad path of grass leading ahead, between the hedges, and I quickly followed it, down to where it turned sharply to the right, and then divided into two. It was not until I followed the right hand path, and passed two more grassy passageways on my left, that I realised I had entered a labyrinth.

I shut my eyes tightly, forced myself to breathe slowly, to keep calm. If I could not quickly find my way out, I just needed to climb over the hedges. It wasn’t barbed wire, for God’s sake: it was only foliage.

It was too dark to follow any tracks I left in the grass, unless someone used a torch, in which case I’d see them coming a mile away. Eventually I came to a halt. I eyed the hedge on my right. It was smaller than some of the others, and looked assailable. Grasping its thick foliage, I tried to pull myself up. It was surprisingly difficult, the branches too flexible to be fully supportive, but at least there were no thorns and it was densely packed. I managed at last to pull myself onto the broad, perfectly cut shoulder, and roll down the other side, landing on the damp ground with a thud. Another hedge reared before me. Well, that was to be expected. I would keep climbing until I got to the edge of the labyrinth and the edge, presumably, of the property.

And so climb I did. Heaving myself up, throwing myself over, dropping myself down, occasionally stabbed by vicious thorns, but more often by unidentified twigs and sharp-pointed, waxy leaves. Once I began climbing a holly hedge, which I quickly abandoned for a more amenable, pleasantly soft and fringed one, that smelled of lemons. I lost count of the hedges I climbed. I could not understand it; I was heading always in the same direction, no deviation, except for when I met hedges of holly or rose, and even then I tried to compensate for any turns I was forced to take.

Hours must have passed. Tears began tracking down my face. I was exhausted, increasingly desperate, swearing aloud at my ridiculous situation. My thirst, oddly enough, had abated, overtaken perhaps by my ballooning fear. Finally, I curled into a ball into the base of a hedge, as far back as I could get to hide myself, and waited for morning.

The dawn took a long time coming. I did not sleep. The ground was as hard and cold as a grave beneath me. There was no moon. But black turned to grey turned to rose, and relief flooded me when I saw the world forming around me once more.

I climbed the nearest hedge and perched on its broad top to see as far as I could. Frustratingly, I still could not see the house. The hedges that bordered the labyrinth were twice as high as all the others, and quite some distance from where I sat. But the labyrinth itself was vast, spread out before me in all directions, and I could see countless hedges melded together into a kind of endless ocean, dusky greens and browns and faded yellows. In the far distance I could see the woods, in all directions, and never had they looked so inviting to me.

I headed towards the nearest border. It was not until I was about two hedges away that I saw something that brought me to a stop. It was not just something, it was someone. Leaning against a hedge, picking at the grass, as if with nothing better to do. I held my breath and stood very still. It was a woman, wearing weird clothes, the kind of thing that you’d see in wartime; austere, grimly functional. Shabby, upon closer inspection.

She must have felt me looking at her. She glanced up, and nodded slightly, seemingly unsurprised by my sudden appearance.

‘So, what year?’ Her voice was cracked and dry, and then, when I stared back at her uncomprehendingly, added, ‘I haven’t seen anyone for days. Care to sit?’

‘You’ve been here days?’ I was incredulous.

She eyed me appraisingly, and sighed. ‘You’ve only just arrived, haven’t you?’

‘What d’you mean, only just arrived? I’m on my way out.’ Fear began crawling up my back. ‘To get help.’

‘Oh, I’m not sure you want to do that,’ she said, as I started to scramble up the huge border hedge behind her. ‘It doesn’t look like a very welcoming century. Especially not for women.’

I stopped pulling myself up, and stared at her. She was clearly insane. Perhaps that’s what had happened to Harold’s mother. She’d got lost in the labyrinth and when he finally got her out, she’d lost her marbles.

I spoke carefully, and clearly. ‘Look, I don’t know you who are, but my friends are still in there. With him, and his mother. God knows what he’s done to them. I have to get help.’ I hesitated. ‘Are you coming with me?’

She actually looked sorry for me. Sorry for me! ‘At least let me explain a few things first. Please.’ The weariness, the resignation in her voice… ‘Before you go.’

So, very reluctantly, I listened.

And then she told me. She told me everything. Of course I could not believe it. I had to see for myself. I threw myself up that hedge and peered over the top. At first, there was nothing much to see, except a lot of scrubland and thick woods – true, much thicker and darker than I remembered – but eventually I heard a clamouring and a thundering and a bellowing, drawing nearer and nearer, until out of those woods in front of me burst a bear; a huge, black, incensed bear, and my mouth fell open as I watched it lumbering across the scrubland, with surprising speed and grace, and then from the woods behind him came three men, carrying spears – spears! – and wearing what can only be described as the kind of clothes people wear in battle re-enactment clubs, whooping and shouting to each other in some incomprehensible language, until they had vanished into the trees beyond, where the bear had fled.

I sank back down beside the woman. I could not speak. How could this be? There had been no bears in England for centuries – well, except for zoos. Her explanation was the only one that made sense. But it made no sense at all.

It was all a time trap, she said. A vast web of time, and that man, that horror, that evil being who had welcomed us into his house, was the spider who had ensnared us. He had no need to follow me. He knew he had caught me, and all the other poor souls trapped inside this labyrinth, from God knows how many centuries past, and for what purpose? Who knew? He was a collector, he’d told us all. But not a collector of clocks. Oh, no! A collector of souls.

‘I can get out!’ I cried, leaping to my feet. ‘I can just retrace my steps; I’m sure I can do it, and find that bastard, and get out the front door, and save my friends, and get him incarcerated, get him put where he belongs – ’

She hushed me. ‘Quite impossible now, I’m afraid.’ Then she told me why I could never go back. The hedges marked timelines. Unless I reversed my tracks exactly, hedge for hedge, turn for turn, there was no way I could find my way back to the house, in the same century, the same decade, the same year. Dozens had tried it. None had succeeded. ‘The only way out of here is over the border of the labyrinth,’ she said. ‘But it won’t be the same time. You won’t know what century you’re entering. And you can’t come back, it seems. At least, nobody has, and plenty have left. I’m still waiting to find a century closer to my own. Where women have a shot at a decent life.’

My eyes slid over her. Her face was smooth, unlined, her hair brackish and tangled, but with no telltale grey. She saw my gaze, gave a wry smile. ‘I’m twenty-eight. Arrived here in ‘forty-one. You won’t age here. Time has stopped. We’re in a vortex.’

***

So here I am.

Tomorrow I will have been here two hundred days exactly. I am never hungry, never thirsty; I do not need to sleep.

I’ve met many people, from many centuries. Some of them I can’t understand at all, the language is so altered.

I have seen three people climb the last border hedge, into the unknown century beyond. One was an elderly woman, who needed my help to climb, and who said with a dry snort, ‘Maybe I’ll find a society where the elderly are still respected,’ as she slid slowly, slowly, down the other side. I didn’t even stay to watch her agonising progress across the flowering meadow.

Usually I’m alone. I watch the changing sky. I’ve lost count of the sunsets and sunrises. The hedges morph into different colours, and grow, and shrink; the spiders spin their traps and starlings swarm in black flocks overhead; I’ve seen that meadow become that swamp, that scrubland, those woods, and I’ve almost forgotten what my year looks like.

***

Come on, then, you’ve heard my story. Now it’s your turn.

What year did you leave behind?

Tell me everything, every detail; leave nothing out.

I mean, let’s face it, we’ve got all the time in the world.

END

Julie Dawn asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

4 Responses

‘All the time in the World’ is a brilliant short story. Great vivid descriptions, which have left a lasting scene of the setting in my head. It’s a dark tale, which isn’t apparent at first, but one that leaves you gripped, and wanting to find out more about the characters, and then it ends! If this was made into a full length printed novel to savour & get lost in, I would snap it up!”

Quite unlike anything I have ever read, amazing and very atmospheric, I could feel almost as if I was part of the story itself.

FANTASTIC- made me want to read more and to know more about the people in the house- i could have read a whole book around this there was so much packed into such a short story, please tell me more!!

really enjoyed.

This is great! I’d love to read a novel based around this premise.