It’s two days after Christmas. Back from the family get-together; life sinking, as it quickly does, back to normal.

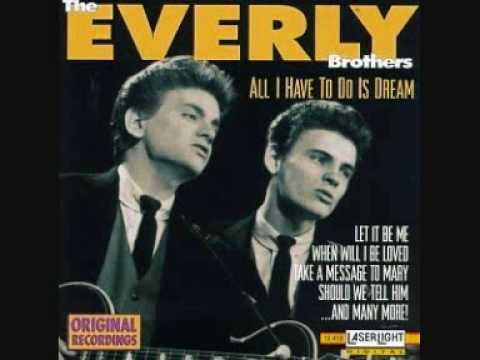

Trevor places the seventy-eight on the turntable of his red Dansette, sets it in motion and, concentrating hard, carefully, slowly, drops the stylus. It’s only just onto the edge of the vinyl, so there’s a second or two of preliminary hiss and crackle. He sits down, watches the disc’s wobbly rotation, a little mesmerised. He knows what’s coming. That brilliant guitar chord, setting you up, expectation piqued, for what’s to follow. Then a moment’s pause. Then the Everlys, Don and Phil, their voices perfectly harmonised. Dre-e-e-e-eem, dream, dream, dre-eem . . .

He lets the sweetly blended voices; the wistful lovesick words wash over him, singing along quietly although he can’t sing for toffee. He smiles ruefully, musing, thoughts turning in on themselves. Why am I so damned sentimental? I’m like a big girl sometimes. Well, can’t be helped. We are who we are. So I like this sort of stuff better than Bill Hayley. Rock Around the Clock was all right. When the film came to town I went to see it along with everyone else. There’d been so much publicity about it, so much outrage in the papers, so how could you not? It was forbidden fruit, almost. The Teddy Boys loved it. There was a near-riot in the cinema. It was as exciting as visiting – in the middle of the afternoon for goodness sake – the Windmill Theatre on that day trip to London with the lads, to gawp flabbergasted at the nudes who were supposed to stand stock-still like classical statues so as to be artistic, but didn’t quite manage it.

But no, he thinks; rock n’ roll’s fine: exciting and new and all that, but when you’re madly in love, your first time, it’s the love songs that really grab you. They do me, anyway. I probably shouldn’t be playing this really. It’s a bit masochistic. Is that the word? It’s certainly bittersweet anyway. Reminds me of Laura. Her sweetness. Her prettiness. Those blue eyes; that thick blonde hair halfway down her back, often done up in ponytails; those soft full lips and that irresistibly soft chest too. The way she really made me feel good about myself; instilled in me a little self-esteem for the first time in my life. Made me walk tall, for all that I’m only five feet five. But I felt like a giant. I was absolutely smitten.

Her name’s the same as that tragic left-behind girl in Ricky Valence’s hit. And how can I forget that first agonisingly nervous time at the youth club when I finally worked up the courage to ask her to dance; having previously been schooled by Carol in the intricacies of jive, over and over again until I got the hang of it, in my bedroom to (yes, all right, I admit) Bill Hayley on the record player.

And how Laura had astonished me by saying yes.

As the Everlys’ dulcet tones rise and fall his thoughts wander. He remembers that first little foray into the uncharted territory of socialising with girls properly, which worked such wonders for his self-confidence, as opposed to the clumsy exploratory kissing and cuddling with girls from school, all two of them, which didn’t really count. And the following Friday night, when she was there again and really seemed to his optimistic sixteen-year-old eyes to be returning his interest. Just one dance the previous time had seemed an enormous achievement and after that she’d retreated to the giggly clique of her friends, although he’d thought he caught her throwing sly glances in his direction afterwards. But that second time had been a quantum leap, when, with great daring he’d made a beeline for her almost straight away, and she’d responded to his invitation with a broad smile and when the record had finished showed no inclination to rejoin her mates. So they’d spent the rest of the evening together. Emboldened, he’d even begun to show off a little, twirling her ever-faster and improvising ever more elaborate dance steps, probably impervious to rhythm. Quite the strutting peacock, he’d been.

He harks back to the climax of the evening as far as he was concerned. The church volunteers who supervised the club tried to keep their charges away from smoochy ballads as much as possible because they could lead into dangerous territory, but someone had brought in the Everlys’ new single, Dream. It had been saved until last, and, as if attracted by a sudden magnetic force the dancing couples had closed into embraces and shuffled around the floor in an approximation of waltz-time, even though the music wasn’t. Laura had come into his arms without hesitation and although they’d had nothing stronger than Coca-Cola, he might just as well have been drunk. He was intoxicated by her closeness, the feel of her body, her sapphire eyes gazing up him (she was only five feet one) in what he was certain was adoration. And the words of the song, which seemed so incredibly apt. They might as well have been written just for them.

He recalls how that had been the start of it all. The next day, Saturday, he’d been straight into the record shop in town – virtually been there waiting for it to open, in fact – to buy Dream. He’d borne it home like some fabulous bounty and pretty well retreated to his bedroom for the rest of the weekend, playing it over and over again. For the first time in his life he’d really wished he didn’t have a brother. One sibling, Carol, would have been quite enough. But in their modest little three-bedroomed house, having Michael as an elder brother had suddenly become a pain. Because, obviously, the boys had to share a bedroom. As the oldest of the three, he was four years Trevor’s senior. And Michael, who was a man of the world and had recently returned home after National Service, hadn’t really taken kindly to his kid brother’s mooning around all the time in their bedroom drooling starry-eyed over some new, highly significantly-worded seventy-eight. It was all right for him though; he’d been going out with Doreen for the last two years, although he hadn’t seen a great deal of her, what with being away in Germany with the army. No doubt he took matters of the heart in his stride now. He was practically a married man.

But for him, Trevor recalls, this was all an exciting novelty. After the third evening at the club, when again they’d automatically gravitated towards each other and he’d made a point of taking Dream along, just in case no-one else did, they’d left together and he’d walked her home, although it meant a much longer walk home for him afterwards. He’d been nervous; he would have been the first to admit it. Dancing and a little light smooching was one thing, but now, he hoped, things were going to get seriously physical. He knew full well that he wasn’t the handsomest boy around; what if she couldn’t bring herself to kiss him? That would be really humiliating. But things were absolutely fine. He’d boldly held her hand on the way home, engaging in what he’d hoped was scintillating conversation and, when they’d arrived, still possessively held onto it, keeping up the chatter, just in case she suddenly evaporated into the night like some wondrous but fleeting mirage.

But then the talk had become a little strained, as if they were putting off the moment of truth. After a while, as the awkward punctuating silences grew ever longer, it had dried up altogether and they’d been left stranded, simply looking at each other. Until she rescued him by making the first move, and reached her free hand up to cup the side of his face and paused only briefly before planting her lips tentatively on his. He hadn’t been able to respond terribly well, but all the same it had led to a longer, more confident kiss and then, to his great relief, a gloriously tactile embrace; a proper one. The process had been repeated several times until she’d announced that she really ought to be going. It was something to do with worried parents, apparently. They’d arranged to meet again the evening after the next and he’d boldly suggested visiting the espresso coffee bar, which had another delight: a jukebox. He’d walked home clutching his precious record in a dream. And thinking rapturously that he’d got an actual, proper, real-life girlfriend! Now he could hold his head up high; compete with the best of them.

He remembers how their relationship (if one excluding full sex could be deemed as such) had gone from strength to strength; the club on Friday nights, the coffee bar a couple of evenings, sometimes the pictures on a Saturday night and, of course, parading around the town and visiting the record shop to crowd intimately together in a tiny booth to sample the latest hits. He’d enjoyed the fact that Laura was nearly a year older. Having an Older Woman for a girlfriend seemed to confer on him an extra gloss of sophistication.

Then, inevitably – although he certainly hadn’t tried to hide it anyway – his mother had begun to take an interest in her younger son’s love life. Intrigued, or perhaps simply to check her out, she’d suggested he bring Laura home to Sunday tea. He’d been all for it; wanted to proudly show her off to the family. Laura had seemed a little more circumspect at first, or perhaps just shy, but once she’d got over the strain of the first family tea, which involved meeting everyone: Mum, Dad, Carol and her boyfriend Denis and a now-single Michael, who’d split from Doreen, and they’d all crowded round the modest (even with its leaves extended) dining table in the dinette, as Mum termed it, because it sounded more sophisticated than alcove (and she wouldn’t countenance the idea of them eating buffet-style), things had gone swimmingly.

Indeed they’d all become great friends. At the first meeting, and every other one for that matter, Michael and Denis had gazed at Laura in barely concealed admiration. They’d laughed at her jokes and flirted very mildly. They could hardly take their eyes off her. Trevor, rather smugly, had felt as pleased as Punch. They were actually admiring his girlfriend! Yes, his girl, who was certainly prettier than Doreen, and a more attractive partner, he imagined, than Denis.

But the friendship hadn’t lasted. Trevor’s thoughts are drawn back to the first signs of strain, when the first cracks had appeared. It had begun with Denis. His constant rapt attention to Laura had grown after a few meetings to become a little too blatant, and Carol hadn’t failed to notice. Hardly surprisingly, she’d grown increasingly and equally obviously displeased. Her attitude towards Laura shifted steadily from friendliness to hostility. Carol was no great beauty. No doubt she felt jealous and threatened. Perhaps she’d decided to get her retaliation in first, because when after a month of Sunday afternoons Denis failed to appear, she darted a venomous look at Laura and announced that she’d sent him packing. So the Sunday teas had rather fizzled out after that. Carol clearly didn’t want Laura in the house, so to avoid upset they’d gone to her folks instead, which was much less fun compared with the joshing jollity of before.

Then, although he’s tried to keep it safely submerged so many times, the black, black memory of the Calamity comes back. He knows now, with the easy wisdom of hindsight, that he should have seen it coming. Her interest had begun to wane. Increasingly she’d seemed to find him irritating; no fun to be with. She’d begun to find excuses for not coming out: flimsy ones like having to wash her hair. Then, to cap it all, Michael, trusted big brother, tall and good looking with his dark smouldering take-you-to-bed eyes and perfectly chiselled face, unlike Trevor’s with its unbanishable acne and imperfectly repaired harelip, had been spotted in a pub in a nearby town, far enough away to avoid detection (he’d obviously thought) with a ravishingly pretty little blonde in tow. The little blonde had been Laura. Trevor’s workmate Billy who’d made the discovery had taken great delight in spilling the beans. Perhaps he was just envious of his good fortune; Billy, with his piggy eyes and knowing leer was certainly no Casanova with the girls himself.

Trevor sadly recalls going home that evening feeling physically sick; numb with disbelief. Remembers how, when his mother had finally winkled out of him the reason for his stricken pale-faced silence, he’d succumbed to impotent tears of rage and hurt, feeling utterly betrayed. How when Michael came in later she’d immediately, brooking no nonsense, rounded on him and demanded to know what the bloody hell he thought he was playing at? She wasn’t going to have her little boy, who’d drawn a shorter straw than his luckier brother in the lottery of good looks, hurt like this. Michael had tried denial at first of course, claiming that Billy must have been mistaken, until Mum had smacked his face, hard, and told him not to lie or there’d be more of that from his father when he got to hear about it. He wasn’t too big for a good thrashing if it was called for, God help her.

So in the end Michael had had to concede that it was true, but he hadn’t meant it to happen; it just had, and he was really sorry. He couldn’t help himself. To which Mum had snorted in derision and told him caustically that young men had no control nowadays. His national service had done him a fat lot of good. Trevor glumly pictures that scene now; his mother lambasting his brother for his selfishness and lack of decency whilst he himself sat mute and humiliated, reduced again to the level of a helpless child. When their Dad had got in from his late shift and been told (Michael having waived dinner and made himself scarce down the pub) he’d been almost apoplectic with rage, and Carol had also hissed, ‘the bastard!’ and ‘the bitch!’ and given him a long sisterly hug when she heard.

He unhappily dredges up the memory of taking himself off to bed, evening meal untouched, sick of all the upset and feeling puny and rejected. Of creeping between the sheets, covering his head and sobbing in his desolation. Of course there’d been no question of Michael and him sharing a bedroom now. Mum had pointedly placed a pillow, blankets and sheets in a sort-this-out-yourself pile on the sofa for his return from the pub, and that had been his sleeping place until he’d packed his bags and moved out a few days later, now the family black sheep, to a flat above a bookie’s.

Trevor remembers how he hadn’t had the stomach or the confidence or the courage to seek Laura out and confront her. What would have been the point? It wasn’t in doubt that she’d betrayed him; thrown him over for a more attractive alternative – and his own brother at that. Just what had gone on, though? Had she taken up with him in the first place as a way of getting Michael later? Had Michael dropped Doreen in order to clear the decks and be ready to jump in when the opportunity arose, knowingly arrogantly that he’d be a much more desirable proposition? He’d never know. But however it had happened, he’d lost her.

So he’d stopped going to the youth club and the coffee bar for fear of encountering her there, although he’d supposed that now she had Michael she’d be doing more grown-up things like going to the pub anyway. And whenever he’d been in town, trailing disconsolately around – not that there was any point in visiting the record shop and buying ballad-type records now – he’d always kept a sharp lookout for her, occasionally stopping short, heart pounding, ready to take cowardly evasive action at the glimpse of a blonde head, although it always turned out to belong to someone else. Later he’d learned (from bloody Billy again) that she’d moved in with Michael, and later still that she’d moved out again. Good, he’d thought bitterly, one or the other of them had now been let down too.

But then Trevor’s memory stream surfaces from the stygian pool of remembered unhappiness; breaks through into the light. He recollects there being a couple more girlfriends in his teenage years, who had restored some pride, although neither of them had been worshipped as helplessly as Laura. He’d probably clammed up as far as new girlfriends were concerned; huddled behind a protective carapace, not allowing anyone fully in for fear of being hurt again.

Until now, that is. Now there’s Brigid. Lovely flame-haired, freckled, stocky, thick-ankled Brigid, with her cockles-of-your-heart-warming Derry accent and body every bit as soft and warm (which he now knows from wonderful experience) as Laura’s (which he’d only got as far as wistfully imagining). Brigid, with a smile never far from her lips and her left leg slightly shorter than its mate, so that she has to wear a rather clunky built-up shoe – either that or limp crazily – which rather limits her wardrobe of shoes. Brigid, named after the top Celtic deity who made the land fruitful and caused animals to multiply; who blessed poets and blacksmiths and whose compassion and skill in miracle working is revered in Ireland to this day, so they say.

Brigid, who appeared, like a miracle herself, ten days before Christmas, like the star in the east, to bring light into his world. Most people wouldn’t give her a second glance in the street, but to Trevor she’s beautiful.

And there’s something else. She absolutely loves Dream. She told him when they met that it was pretty much her favourite single of 1958, if not of all time. That had clinched the attraction. She makes no apology for being sentimental either. It’s because of being Irish, she confesses with a grin. Hearts worn on sleeves, and all that. He loves her for it.

He suddenly realizes that the record has finished and he’s missed it through being so lost in thought. So he puts it on to play again, and croons softly again, absorbing the words, now directing his thoughts only to Brigid.

In fact here she is now, entering the den, his domain, with its bookshelves and memorabilia, bringing a cup of tea and a plate holding a slice of Christmas cake and a slice of stollen. She puts them on the desk and places a somewhat arthritic seventy-nine-year-old hand on the nape of his eighty-year-old neck.

‘Sure you’ll wear that record right out if you play it much more, so you will,’ she murmurs.

Trevor glances up at her fondly. ‘Yes I know. It was hearing it the other night on that programme about hits of the fifties and seeing the Everlys again, with their smart suits and Brylcremed hair. They looked so young, didn’t they? Just boys. It took me right back – not that I was ever as good-looking as them. I was just reliving the past.’

He pauses, a wry, wistful smile playing across his lips.

‘I was just dreaming.’

END

John Needham asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

3 Responses

Who of us hasn’t felt like Trevor about our first teenage love? Adoring of Laura and worshipful of her above everyone else, his heart is only hers. But, no one is perfect, not even the one person he thinks personifies it all. Trevor learns this in a most hurtful way and from a person whom he should have been able to trust implicitly. A tough lesson to learn, but one that teaches him that life goes on, time helps heal the pain and beauty is only skin deep.

With The Everly Brothers beautiful song resonating in my head as I read it, it brought back all of the angst of being a teenager in love. As with all of his stories, John Needham gives us another unforgettable one with a most satisfying ending. One that I didn’t see coming, but one that was simply exquisite. This is another one of his short stories that should be cherished and read over and over again.

A wonderful story tracing the arc of a lifetime. Young love and the unavoidable loss involved, yet without sentimentality. I especially admired the way the author comes full circle toward the end of the story, when Trevor and Brigid, now in the autumn of their life, demonstrate their mutual affection for one another through the song. Superb threading!

Thanks for the very kind words, Philip.