It was a good day when I beat Antonia Somerton in the Art Exam. It was also incredible. When Mrs. Cooper called out the top two marks, Antonia got 68% and I got a once-in-a-lifetime 76% and for a moment neither of us reacted. Then I snatched my still-life (‘Three Daisies in a Vase’) from Mrs. Cooper’s hands and stroked the pencilled mark to make sure it was true. Slyly glancing at Antonia’s face, I noticed with satisfaction her sullen refusal to look at her mark, as she took her work and flipped it facedown on her desk. My classmates, not collectively overjoyed to find me top of the form, were, nevertheless, delighted that Antonia wasn’t. A rare, warm glow of success kept me going all the way through Spanish and History, only to inevitably fade away through a double session of Chemistry, where Antonia resumed her rightful place as a pearl amongst swine with a truly awesome 98% for the recent test paper on chromatography.

When I was seven years old, my primary school class was asked to try to imagine ourselves when we were eighteen, where we would be, what we might be doing. I had said: “I’m going to be a window cleaner with a monkey, and we’re both going to wear dungarees and wash windows together”. Seven years on, I knew the monkey option was out, but I hadn’t come up with any terribly bright alternatives. But due to my father’s different overseas postings, this was my ninth school, and I had at least learned how to fit in at all costs. Skating under the radar, I made friends fast, could take a joke and avoided prefects. I liked English, and clearly, I wasn’t that bad at Art. All other subjects could go hang. Antonia sat behind me in our classroom – Somerton followed Saunders – and that probably irritated her, too.

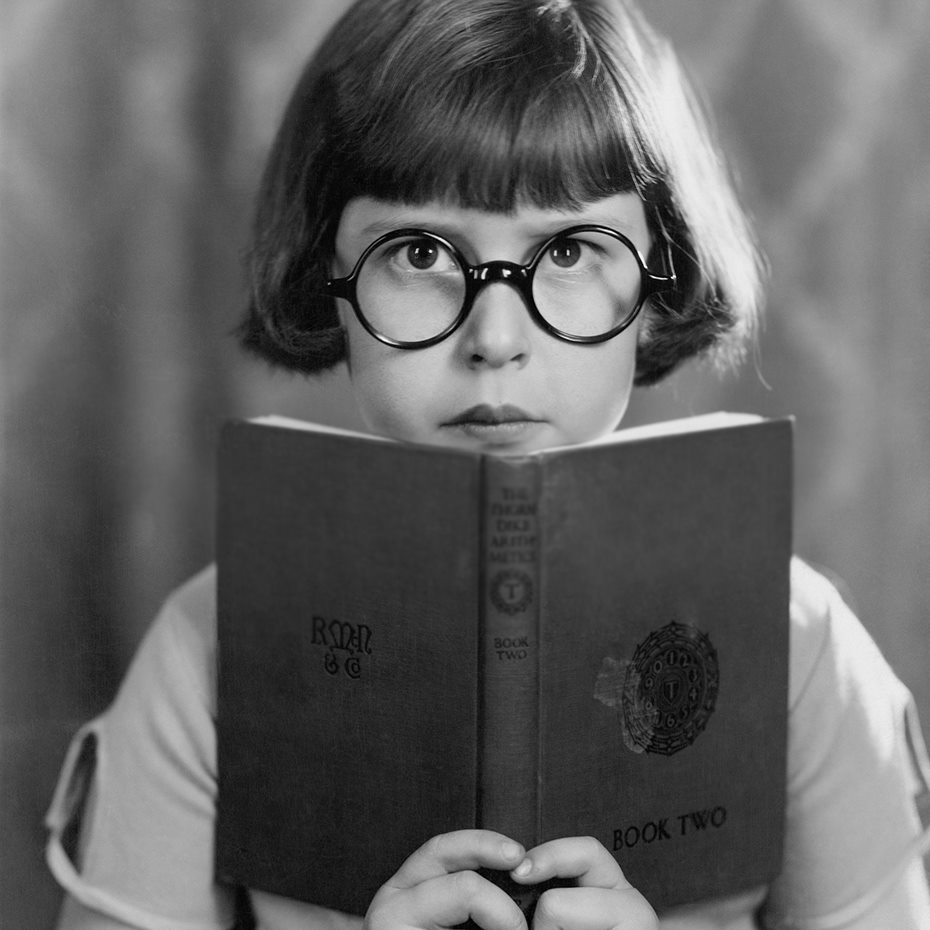

“Can I borrow your sharpener?” I spun round one morning and looked at her. Apart from an awful first name, Antonia had dull brown hair cut in a neat pudding bowl shape, a pale face, and cow-like eyes that blinked behind her pink National Health glasses. To be fair, this dreary description could have been applied to many others in my school. In fact, I had the same glasses, probably chosen by my mother to physically churn the stomach of any randy teenage boy who just might have thought about tearing my clothes off upon spying me in Smiths or the local record shop. For this reason, I never wore them, and went around outside school grounds permanently squinting. Antonia never took hers off, and now calmly lifted her eyes from her immaculate handwriting to regard me with thin-lipped disapproval: “I want it back immediately,” she hissed, “you really need to find yours, Tanya.”

It was perfectly in order that Antonia should go straight into Div 1 for Maths and that I should be hurled into the pit of Div 4 with a bunch of other no-hopers. My father ruefully commented: “You’re a bit of a duffer, aren’t you? Well, you’d better marry someone practical”, and he punched my arm lightly and turned back to his crossword, shaking his head in bemusement. I hated Maths. A combination of genuine bafflement, wilful misunderstanding and boredom meant that I spent a lot of time dreaming about more interesting things. Specifically, my first kiss.

Ironically, I had Antonia to thank for this mind-altering event. One rainy Friday breaktime, we were slouched around a table eating biscuits and looking forward to the weekend, when Miss Lush, the sports teacher, bore down upon us. Lush only in name, she was a stocky, red-faced young woman with wiry, prematurely grey curls and a brisk, relentlessly upbeat manner. In case you forgot what term it was, Miss Lush’s eye makeup would serve as a constant reminder – metallic blue in the Autumn, metallic green in the Spring. Iron Kingfisher Blue now flashed as she pounced: “I need two volunteers, Tanya, Antonia – you’ll do – to collect two bags of hockey sticks from my car. You’ll need your macs. Chop chop”. I scowled and Antonia looked impassive. As we headed towards the car park, she looked at the teeming rain and flatly announced: “I’ve just remembered. I’ve got Extra Maths coaching right now. It’s very important. You’ll have to do it yourself.” And began to scuttle off in the direction of the Library. “What if I had something important to do?” I complained to her rapidly receding figure. Without stopping, she briefly looked over her shoulder: “That’s easy, you never do.” I reached the car to find a teenage boy getting out of it. “Have you seen my aunt, Caroline Lush?” He stared at me, and my heart jumped. Annoyingly, my voice became a squeak: “She’s sent me to get the hockeysticks, actually. I’m Tanya.” And I cursed the fact I was wearing my purple Milletts cagoule with the swinging plastic toggle that hit my nose every time I turned my head. “I’m Luke. No worries, I’ll help you carry them in.” Thank you, Antonia.

Luke was probably the third boy I had ever spoken to and had no spots or glasses. These last two alone rendered him instantly desirable and when we parted, and he casually said: “Do you ever get allowed out?” I knew he would be The One. A week later, sitting in a secluded bus shelter, shivering from the November wind or sheer anticipation, we kissed. It was terrifying, delicious and his maleness overwhelmed my senses. Later on, as I sat in the Library, absentmindedly watching Antonia cross-referencing numerical data, I re-read Luke’s message. It was written on a notelet with a labrador on the front. The labrador had a speech bubble coming from his mouth which said “I Wuff You!” I knew it would last. I rang him on Christmas Day and got his mother, who didn’t sound very pleased. He never contacted me again, and I returned for the Spring Term and exams, with pierced ears and a new restless attitude. I had found a copy of D.H Lawrence’s ‘Women in Love’ on the empty train seat next to mine, and for a long while tried to do my hair like Gudrun.

The mocks, bar English Lit, were a nightmare. I stared, panicking, at the hundreds of photocopied pages of Physics equations which I had neatly filed away and then never referred to again, and decided that, to save precious time, I would concentrate upon revising for the History exam. Dear God, who knew there were so many bloody five year plans? I couldn’t even organise a four week revision process. I got 73% for my ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’ essay but Antonia got 78%. In Latin, she got 100%. As we all goggled at her, she smiled modestly, and bit her lip. The elderly Latin teacher (“Salve, Mr. Edwards!”) and the only man allowed to be on the school staff because he was eighty-two and had a stick, marvelled at his protege: “Well, I must say, Antonia, you really have achieved a magnificent result!” Eyes blank behind the glinting spectacles, she replied proudly: “I recite a poem in Latin to my father every Saturday at lunch, and then I get my pocket money.”

The summer term began with more revision for our now important public exams. Having belatedly realised that I was simply going to fail all sciences and geography – and having given up Latin – I decided to focus on a very few core subjects. I knew that I didn’t want to continue with school in any way, shape or form. At night, I read ‘Madame Bovary’, ‘Crime and Punishment’, ‘Don Quixote’ and my first American novel, Kate Chopin’s ‘The Awakening’. My English teacher said that it was distracting for me to read such novels when I should be concentrating on our set text, ‘Kes’. The depressing ‘Kes’ was reserved for the silent mandatory hours in the library, often glumly opposite Antonia. As my mind flitted like a moth, hovering and softly landing randomly on this worksheet or that novel, I saw grimly that Antonia was made of sterner stuff. I was now faced daily with the reality of a person who could bend her mind to any academic subject in hand. Her concentration was astonishing, her eyes rapidly scanning vast amounts of information, storing it for future use. She rarely looked up unless it was to check the clock. I noticed that, every 45 minutes, she would carefully close one lever-arch file to open another. A pile of small pamphlets entitled ‘Oxford University Test Papers’ now sat in front of her. Her discipline and drive was admirable and terrifying.

I left the school at the end of that term, with a disquieting sense of relief mingled with foreboding. My parents were going to Sao Paolo on a two year posting, and because I didn’t know what else to do, I went with them, announcing to classmates that I was going to party. I went to say goodbye to the librarian, the only member of staff that I had ever liked, but found that Antonia had now taken up residence, alone in the room, piously labelling and stacking bookshelves. In a rush of new-found shyness and generosity, I said: “I’m off now, good luck Antonia, I’m sure you’ll do brilliantly!” She barely looked up, but muttered “Thanks. Bye.” I spent most of the long flight to South America reading ‘The Dice Man’ by Luke Rheinhardt, and told the man who sat next to me that I had left school for good. “Were you naughty at school?” he said. “Sometimes,” I replied, looking straight ahead. “Did they spank you when you were naughty?” he said. I told the air hostess I wanted to move and she said ok.

I managed to get a part-time job working in a leather goods shop for a tiny, fierce Spanish woman called Senora Vaccarez. She told my mother “she has nothing to offer me but quite nice hair, but don’t you worry, I’ll sort it.” I learned more about South American knitwear than I wanted to but I did pick up Spanish. Before I could settle properly and decide what to do with the rest of my life, my father announced that we were coming home to England, specifically to Oxford where he had been posted to start up a new office for his company. Senora Vaccarez announced that she could get me a job, in her cousin’s little gift shop that was based in North Oxford.

One Year Later:

I heard the string of bells tinkle against the shop door with pleasure. They were a domestic, reassuring reminder that I was needed, my attention was required, and I hurried through the bead curtain to the front of the shop. A young blonde man, quite tanned and wearing a bead necklace, came into the shop. “Er, hi,” he smiled, “I was just wondering, I speak Spanish and I wondered if there were any part-time jobs. I’m a student, you see…” Quickly, I put him straight. “No. No. I’m the only one who works here and Senora Vaccarez, she’s my boss, she comes in sometimes and does the accounts. She owns it, you see. I mean, we don’t sell that many llama jumpers, ha ha, they’re not leaping off the shelves… sorry.” His face dropped. “Never mind, thanks anyway,” and he ran his hand through his thick hair, and turned to go. My heart stopped, and I thought, “Now or never”.

“You could try next door, the bookshop. They sometimes need people. I could ask the manager for you, I know her a bit.” He turned, and looked at me properly and smiled widely. “That would be so kind of you, I really need to get something.” I took his mobile phone number and said that I would call him later. I didn’t even ask his name. Later on, I called the number. It went straight to voicemail and I left a message: “I managed to get you an interview. Please call Terry Bradshaw on this number tomorrow and arrange a time. So, good luck.” I clicked off reluctantly, wanting to retain the tenuous connection.

Two days later, I was tidying up the panpipes after a group of small children had been enthusiastically blowing into them. The blonde student walked in and came straight up to me. “So I got the job!” he announced. “Saturdays and one afternoon a week. You must be a great saleswoman, I owe you big time.” We went out for pizza to celebrate. His name was Simon and he was a first year student at Oxford Brookes studying architecture. We talked for hours and I fell in love instantly. We agreed to meet again after work on Saturday, but as I had just opened the shop that day, he came in swiftly. I thought he was going to cancel our date and I saw the floor open up before me, but he put a paper bag down on the desk along with a takeaway coffee. “Thought you might appreciate these. See you later.” He grinned and disappeared before I could recover myself. I spent the rest of the day writing ‘Simon, Simon, Simon’ over and over on wrapping paper.

We started to see each other properly. Senora Vaccarez commented that I had colour in my cheeks, that I seemed different. She looked at the books approvingly: “You’re doing well, young lady. I like the way you’ve decorated the front window and you’re selling more stock, even those little tasselled hats… I wasn’t sure about those.” I moved out of my parents’ house and into a flat with three other girls over the other side of Magdalen Bridge, and every day I now jumped out of bed with a zest for life that I had never known. It was perhaps six weeks after Simon and I had started to go out, and a Saturday morning. We had cycled to work together and I turned to him as we locked up the bikes outside our shops: “I’m so happy, you know.” A couple of hours later, I had made a cup of tea and now gingerly carried the full cup through to the front of the shop. As I put it down, there was a blur of movement through the window and a terrible crashing sound. A screech of brakes and somebody screamed. All at once, it seemed as if the whole street was alive with people running past my door. Feeling a panic take hold of me, I yanked open the door and ran outside. A lorry had crashed into the bookshop where Simon worked, narrowly missing the corner of my shop. There was dust and rubble and people scrabbling at something under the nearside wheel of the lorry. I clutched at a woman, who stood paralysed on the pavement, her hand over her mouth. “What happened?” I cried. “There’s a man under the lorry, it just caught his wheel, he didn’t have a chance!” She stared wide-eyed at me. In my heart I knew that it was Simon. I think I was screaming. I don’t remember, but I tried to fight my way through the group of people surrounding the twisted and bloodied shape half-hidden under the wheels.

There were books spilt everywhere. Someone shouted “It’s not a man, it’s a woman. Get an ambulance, for God’s sake!” I stopped, overcome by shaking and sat down heavily on the ground, feeling sick. My hand felt something smooth and I looked down blankly to see what it was. A maroon workbook with writing on the front. Picking it up, I saw the words ‘Antonia Somerton. Classics. Somerville. First Year.’ When Simon found me, I couldn’t stop crying for hours. “You’re in shock,” he said kindly, hugging me tightly. “You poor girl. It’s a horrible thing to see something like that. I promise you, she’ll never have known a thing about it, they said she would have been killed instantly.”

He just couldn’t understand why I couldn’t stop crying.

END

Nicky Catton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work