My uncle with the close-set eyes that at times roved sideways, as if seeking to escape his head, lived in the warehouse district of Toledo, not far from a Pizza Papalis and a Blarney Irish Pub. He said that Toledo was closer than the moon. He always said things like that, which made us scratch our heads or want to save a jar of pennies for a rainy day.

He couldn’t hold down a job, lived on government checks and whatever money my parents sent him. My father blamed much of it on a ‘poor attention span.’ I’m sure that the big shots who wrote the psychology textbooks had other names for it.

His name was Joe, but my father called him Uncle Grim (but never to his face) because he hardly smiled. He never even laughed at his own lame jokes. Like how many eggs does it take to hatch a chicken?

Answer: One yellow one.

And more often than not he was quiet, contained within his own dense silence.

We lived in the Old Orchard district which my father considered safe to raise a family. Near us was a public library and a Schorling’s grocery store. Our neighborhood sprouted lawyers and university professors such as my father, who taught introductory philosophy courses to wide-eyed freshmen. I sometimes peeked at his lecture notes, doted on names like Sartre or Descartes, and thought how many geniuses it must take to make an idiotic conclusion about life and its variant meanings or that it had no meaning. I imagined that the housewives and the baby sitters in Old Orchard were content to live life behind shopping carts and a brand name of sunglasses. Our neighborhood was safe but life-sucking.

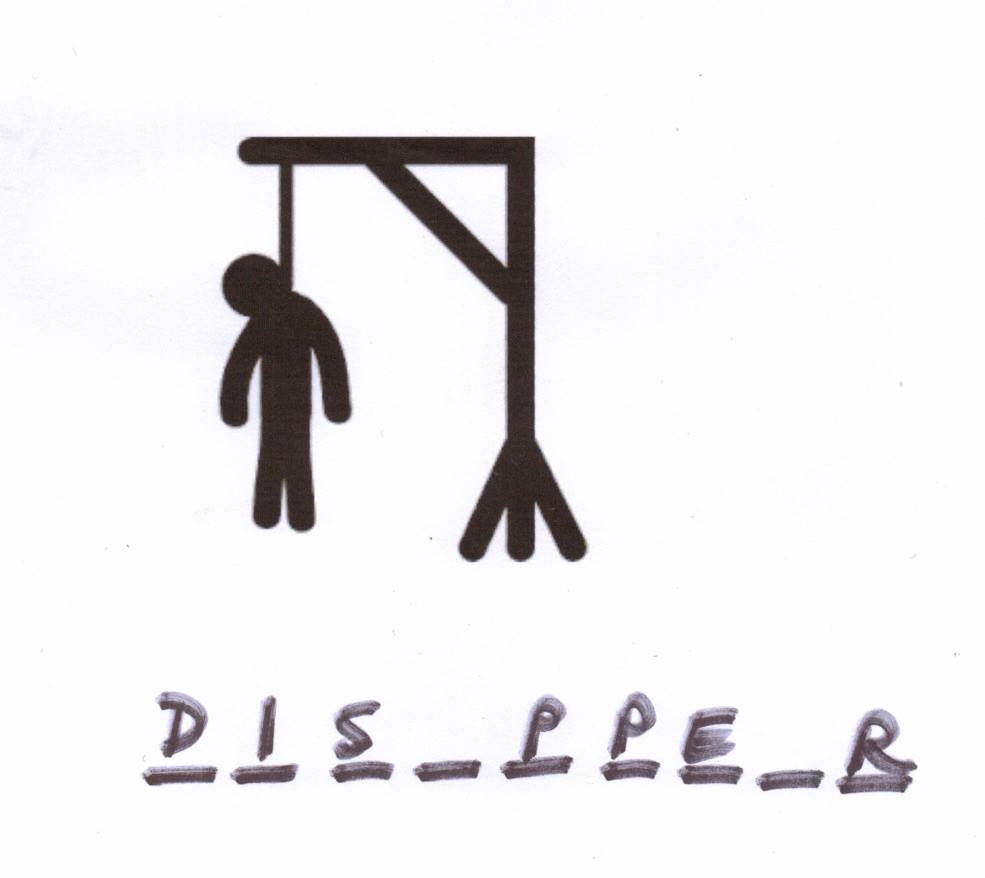

I lived in my room mostly. I hated the bullies and their Slurpee addicted girlfriends with a strawberry or peach-colored rash around their lips that almost looked obscene. In that second-floor hide-a-away, I invented my own puzzles, or pretended I could split into two people and play Hangman. The great thing about it was that I couldn’t lose. Imagine, I thought, making the stick figure of a man disappear by spelling a word I already knew. That man was me.

Whenever I spelled the word ‘Grim’, I’d disappear.

I wondered if Uncle Grim ever played Hangman on rainy days. He sometimes had this vacant stare, as if somebody inside his head was spelling a word, the name of someone or something he once destroyed or destroyed him. Maybe that’s why he chain smoked and lived on instant coffee.

His teeth were so yellow and sometimes he wore the same checkered flannel shirt from the day before. My mother, his sister, grew tired of berating him, and she offered to do his laundry. In return, he brought her extra cartons of cigarettes, which he got from some war vet acquaintance of his, who was always selling things like jewelry, clothes, record albums, at some insanely cheap price. Uncle Grim never revealed the seller’s sources when my father asked him. Only my father would ask those kinds of questions.

“He wasn’t always like that,” my mother said, returning home one day from her monthly book club at the local library.

“Wasn’t always like what?” I asked, tapping my pencil against a Freshman Intro to Algebra textbook that made no sense. Hangman was so much more linear.

“He had a nice set of teeth and beautiful wavy hair. He took care of himself. And blue eyes that could make a girl fly away. In those days, he was a real catch.”

“Like Paul Newman?” I said.

She headed towards the kitchen, mumbling something about calling a neglected friend who recently had a mammogram.

Uncle Grim was a Vietnam War veteran who supposedly flew bombing missions over Hanoi and enemy ammo dumps. The story went that his plane was shot down and he spent some five months in a Viet Cong prison camp. He escaped with a fellow prisoner who later took a bullet for him two miles from a U.S. army base. I always wondered whether Uncle Grim wished he had bit that bullet instead.

Uncle Grim never married, and after returning from the war, he drifted, maybe the way I drift from day to day. Only he drifted wider- West to East- settling somewhere in the middle.

His apartment became my dirty heaven. Besides the cigarette smoke and dust, it smelled of exotic places. He said it was a mix of Balm of Peru and Ginger Co2 oil. He said it helped him forget.

I didn’t probe.

We often visited the arcade playing pinball or munching on pizza or beefsteak sandwiches with roasted peppers. Or we sat in silence on a park bench, even when it got cold, even when it drizzled. It was our way of forgetting.

And one late afternoon, after treating him to a corn beef sandwich with chips, (I usually treated him with what leftover money I had from doing odd jobs in the neighborhood), I asked him if he ever played Hangman.

We stopped at the corner of an empty intersection. A cigarette burning to its unfiltered tip sat between his lips. He spoke without looking at me and was wearing an old Dodgers cap, even though he didn’t follow baseball. He must have picked it up from a flea market.

“No. Some of the guys back in the service did. Why?” He turned to me. His eyes had that familiar vacant stare.

“No reason. I do. I mean I play it sometimes when there’s nothing to do.”

He shrugged then walked briskly across the street. I followed at a more leisurely pace. At the steps to his apartment house, he turned, brown eyes lingering on my face and said I had mustard on my chin. Later, in his suffocating space of a dining room, I told him how much I hated school, how much I hated my life.

“As if I didn’t know,” he said, then heated some water to make instant coffee.

The days followed each other like dominoes. I lost myself at the arcade, shooting little metal balls, trying to hit the make-believe lions and tigers. Uncle Grim would sometimes stand outside with hands in the pockets of his baggy gabardine trousers, surveying the clouds or the people below. I’m not sure if he ever reached a conclusion about either. Or if watching some news coverage on the war with Iraq, he’d get up, stand in a corner of the room, and mumble to his shadow. I rose and changed the station.

At school, I avoided the teacher’s eyes. I had pimples that came and went and a lousy pitching arm. Teachers humiliated me for not knowing an answer and with other students, the ones I tried to get close to- I had a way of putting a foot in my mouth. Maybe I inherited that from my father is what my mother said. Wesley High was a prison term of reading assignments I couldn’t get through. I visited Uncle G more often. Back home, I became the greatest solitary player of Hangman. I was losing weight, skipping snacks. Before a mirror, I thought- you’re getting ugly.

Popping up one day in his apartment of basement-bargain furniture and assorted knickknacks from garage sales, the small TV that sometimes flickered, the one that showed his favorite black and white comedies (I Love Lucy, Ozzie and Harriet), I said, “Wanna play some pinball?”

He said “No school? You’re early.”

He winked.

And one day, I found a long stretch of cord on his bed with one end made into the shape of a halo.

I asked him what it was for.

He shrugged, said he was working on something that could reach soup or fruit cans on shelves too high.

I didn’t believe him. But I wanted to.

I kept thinking about that piece of cord.

From then on, whenever I dropped over, I searched for that cord, wondered whether its loop had become bigger or more taut, if it was now a different shape. When I found it in the third drawer of his dresser, I hid it under his mattress. It became a kind of unspoken game between us-me, hiding the cord, him, always finding it, placing it in a different location.

I dreamt of him flying a jet fighter towards a gigantic loop. I never finished the dream.

Weeks later, I worked up the nerve to ask the big one.

I said, “Do you ever wish the world would stop?”

He parted his lips slightly.

“You mean like a yo-yo? Like a yo-yo you just get tired of and put in your pocket?”

“Maybe. Or maybe if I’m the yo-yo and I want to cut the string.”

I felt stupid saying it. Maybe I had put too much of myself in Uncle Grim.

His eyes rolled to one side then back looking straight through me. It gave me a chill.

“You mean end it? No player, no more yo-yo. Is that what you mean?”

He rubbed the back of his hand under bristled chin.

“I guess that’s what I’m asking.”

“Why?” he said, “do you? Do you want it to stop?”

I stood before him rubbing my lips together.

“Sometimes,” I said.

“Everybody does. I mean, sometimes.”

“Why would you want to end it?” I asked, as if I couldn’t guess.

He tilted his head and squeezed his eyes, looking at me as if I were some wise guy. A wise guy with pimples and wet feet.

“Did I say I wanted to end it? Maybe you do. Maybe you see too much in your sleep? Kiddo, you have a nice life, a nice mom and dad. You got a future. Why mess with it?”

“Because there’s nothing. Not because of something. My life is one straight line that never ends, never reaches anywhere. That’s how I think of it. Maybe saying it stopped is saying the same thing.”

“Wow, that’s heavy. You must be reading those French philosophers your father quotes from after his third aperitif. Those people with their thick reading glasses live inside their heads,” he said.

“Don’t most people?” I asked.

I looked down at his brown Oxfords, a size too big for his feet. He once claimed they gave his feet room to breathe.

“Say,” he said, “I have an idea. Why don’t we do it together. No fun doing it alone.”

“You serious?” I said.

“Serious as shit, as death. We can do it right now. Put an end to all of it. Cut the string to the yo-yo.”

He made a cord with a loop at each end. This one was thicker than the others. He slung it over a ceiling pipe in the kitchen. Then, we climbed upon chairs and placed our heads in each noose.

“You go first,” he said. “This way I’ll make sure you don’t cheat.”

“The pipe won’t hold,” I said, testing its strength.

“You’re chicken,” he said.

“You are,” I said.

“You’re a lazy chicken who’s afraid to live.”

“You sound like dad. An abbreviated version.”

I bit my lip.

“Here goes,” I announced.

He didn’t seem nervous at all, as if everything about me was so predictable.

I bent my knees and exhaled all my air.

I jumped.

It didn’t quite work.

He caught me, pulling at my shirt.

“Son of a bitch,” I said.

He undid the noose around our necks.

“Wanna play some pinball?” he said.

Over the following weeks, I wore turtlenecks, high-collared shirts buttoned up, so mom wouldn’t see the red marks around my throat.

Several weeks later, I learned that Uncle Grim, the once decorated bomber pilot, had hung himself.

I couldn’t bring myself to attend the funeral. I stayed in my room that day. My parents were probably the only ones who went. My mother didn’t cry or get real dramatic. She mentioned later that she always knew something like this would happen sooner or later. My father never said much about it, but for weeks, he kept misplacing his lecture notes or became very quiet while driving us for ice cream on Sundays. Usually, he talked up a storm. But I blamed myself for being so careless, for bringing up that conversation with Uncle Grim about stopping the world. I had sabotaged a part of myself. And maybe he saw part of himself in me. Maybe he saw something worth saving.

I grew up and moved out of Toledo. My first job was in the collections department of a large insurance firm. I dated a girl who I didn’t exactly love but sex with her was like diving into a pool of clear blue and white reflections. When I came up, I was breathless and wanted to breathe. I lived alone in a bigger apartment than the one in Old Orchard, which meant that I was surrounded by more space. I still had too much time on my hands. I still wanted to be someone else or maybe no one else. And whenever I thought of Uncle Grim, every now and then, I became moody, irritable. I ended relationships with the flimsiest of excuses, then I hated myself. I thought of taking up hobbies that would distract me. Like skydiving. I never did. I was too chicken. But I dreamt of falling from a plane and down below, Uncle Grim was waiting to catch me with arms spread out. In some dreams, we played Hide and Seek and I could never find him. On some nights, I went dreamless. I’d wake up smelling Balm of Peru. No, I didn’t develop much of an interest in hobbies. But I never gave up playing Hangman. Some part of me still wanting to disappear.

END

Kyle Hemmings asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work