Hebden Road ends abruptly. It’s as though it ran into a brick wall. Which is exactly what it did. Marketing “The Pastures”, a seventies private housing development, the admen accurately tagged it “exclusive”: the council estate inhabitants where I grew up were excluded from the rusticated well-heeled by a ten foot boundary erected by the developer. One small step for man transformed, overnight, to more than a giant leap for tenantkind. It became a mile and a half’s trek to cover the same distance you could have previously have reached comfortably by spitting.

Upon retiring as Matron of Powick Hospital (formerly Worcester County Pauper and Lunatic Asylum), Auntie Jess bought a new house in The Pastures, “to be near her sister, Lucy”, who was my mother.

Jessie Merrefield. The sort of name given by a screenwriter to an English art-dealer con artist, who chokes on a fishbone in the second act. I don’t remember Jessie dying. I don’t remember her moving to Wiltshire. I do remember her sandwiches.

Jessie lived backwards. She traded youthful altruism and rigid self-discipline for self-indulgence in later years. A religious woman, her only love was the longed for but unobtainable celibate, Father Newson, who visited and ministered to the inmates in Worcestershire. A framed photograph of the bespectacled cleric, looking devout, wearing a tricorn and his dog collar, carrying the Holy Bible stood next to her television. In later life, she let go; Jessie took up chain smoking; acquired a Scottie dog, which having been fed only steak, farted lethally; and compulsively watched all-in wrestling on daytime TV. Big Daddy and Mick McManus tore one another’s guts out under Father Newson’s reproachful gaze.

Just a schoolboy when she arrived, I see now that I witnessed Jessie’s decline without understanding what was happening. Why did she relocate to Westwood? In retrospect, Jessie feared for my mother Lucy, because my father, John, then fifty something, had inadvertently fathered a son with the lodger shortly after my birth. It might have been preferable if my initial diagnosis, fibroids, had been borne out instead of me. Had I not been born, Lucy might have been brave enough to divorce John. But couples tended not to separate in those days: Lucy was seemingly at John’s mercy. She needed protection from him and from the consequences of his propensity to play away, or so Jessie concluded. But did she? After all, although my three grown sisters were able to support themselves, they were still at home supporting their mother.

Jessie thought the unruly ne’er-do-well branch of her family needed to be taken in hand. Her sister’s brood lacked order, a figure of discipline. John had forfeited that role, neither to be reinstated nor forgiven for his dalliance. So Jessie played a self-delusional game of carrot and carrot; actually carrot and stick. We were invited every Sunday to high tea at Jessie’s, lured by her colour TV (rented from “DER” which she pronounced “duh!”); she mistakenly believed that the mountain of food she supplied each time was equally compelling. In fairness, the set compared favourably with our 405 lines black and white job, fitted with its own magnifying glass to make the diminutive screen look bigger. The meal, however, was not the treat Jessie imagined it to be. And it was a mile and a half riding Shank’s Pony each way, thanks to that accursed brick wall. Every Sunday.

Jessie had done her utmost to rehabilitate the reputation of her humiliated younger sister. But these efforts met with mixed success. Lucy was invited to The Pastures to share a morning cigarette with Jessie while she entertained the neighbours. Building on this social success, Lucy was invited too, to Jessie’s Bible reading circle. This was less fruitful. Lucy prepared a talk praising Adolf Hitler for raising Weimar Germany from its knees and putting the country in a position to fight a World War. She wasn’t invited back.

The real battleground for the (re-)establishment of social order, though, was Jessie’s high tea. How my elder sisters escaped the ordeal, I never discovered. This left me, however, with Lucy, Jessie and other elderly guests from The Pastures. The ritual never varied. The sitting room net curtains twitched as we approached. We were seated on heavy lime green sofas and chairs each with an uninterrupted view of the DER, and treated to “Stars on Sunday”, a quasi-religious programme presided over by Jess Yates who, it subsequently transpired, had done a fair bit of philandering himself. We watched through clouds of thick cigarette smoke which made my eyes stream. All the while, to one side of the DER, adjacent to Father Newson, the Sunday spread lurked under a table cloth.

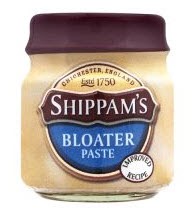

After the last prayers were sent heavenward by TV Jess, t’other Jess invited us to sit up, the upper table cloth was removed, and the clandestine feast revealed. It was always the same. Apricot mousse made with Carnation (homage to post-war rationing; “always we must be worthy”) and sandwiches fashioned from Mother’s Pride, margarine and fish paste filling. Looking back, I see that the sandwiches had to be made thus, since I was the only diner in possession of my own teeth. What really sealed the fate of those occasions, however, was the fact that Jessie was a planner. Such was her lively anticipation of these soirees, that she left nothing to chance. She made the sandwiches before Sunday breakfast. By the time they were unveiled, a mixture of stale breath and nicotine infused them, and their three corners had moved nearer to God. It appeared as if Father Newson’s tricorn had miraculously multiplied and through a process of transubstantiation of sorts, made bread, but not flesh.

They petered out, these “dos”, as it became clear that Jessie’s neighbours were permanently otherwise occupied on Sunday evenings. We were no longer invited, and Jessie lost her sense of purpose, slipping into a sad decline. That’s when the interest in wrestling began, and smoking became a sport.

Jessie had the last laugh, though. Each Christmas, the extended family attended Bath pantomime. Just as the curtain rose, the rustling of silver foil could be heard throughout the auditorium. A dozen fish paste sandwiches were ferried along the row until we each had one. Corners curled up with deference to Father Newson’s hat.

END

David Prosser asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work